"Tum tata log bilkul isstudy nahi karta hai!" thundered Ms. Nathaniel at Manzoor and Jaffer, two of the several Hazara boys in her class. It was either 1978 or 1979. Years later, after I had graduated from St. Francis' High, whenever I thought of her she reminded me of the many colorful, and at times devilishly conspiratorial, Anglo-Indian characters in the short stories of Saadat Hassan Manto, probably the greatest of short story writers that the Sub-continent has produced. The boys at the receiving end of Sylvia Nathaniel’s trademark rage on that day had not done their homework and were getting a dressing down by her.

The word “tata” was often used for Hazara students at the school and most of the time it was more of a marker than anything else, with not much special meaning, either positive or negative, attached to it or implied by it. As is the case with all such words and labels, the contexts in which it was used-----the people, the relationships, situations, the tone of language used, gestures etc.-----were more important than anything else. Change the context, or the parameters that inform that context, and what was once a term of endearment will quickly become a poisonous insult, a vicious slur on identity, an odious gibe about some weakness or disability and so on. Imagine a man calling a stranger a monkey (bizzo or bandar), a grasshopper (malakh, tidda), a kitten (pisho or billo), a puppy, a gorilla, a pony or even a donkey (khar, kharro or gadha), motay, chotay, thothay and lamboo etc., terms that he uses daily for his children at home. Ever wonder why many best friends use the most abusive of terms for one another? They do it not because one wants to insult or degrade the other, or even the other’s mother or sister in some cases, but because of the great love that they have for each other. Among Hazaras themselves “tata” can mean any of the following: a tradition-bound old man, an elder; an ordinary, no-frills dude; an honest, hard-working fellow who minds his own business and does not care much about the world around him, somewhat like the takari of the Baloch and the Brahvis.

Wikipedia tells me that St. Francis Grammar High School “was established in 1946 to provide education to the elite of Baluchistan and Sindh.” A Roman Catholic missionary school situated on the famous Zarghoon Road (formerly Lytton Road), it is one of the oldest educational institutions of Quetta and has produced many luminaries from a former prime minister to army officers, politicians, writers and ambassadors. There is not much available online on the history of the school and I will not dwell on it since that is not the subject of this blog post anyway. Christian missionary schools were everywhere in Pakistan in those days and there were at least six or seven of them in Quetta at the time we matriculated---in 1983. The “we” here refers to my class-fellows (classmates), some of whom I clearly remember and will introduce them to the readers in the following paragraphs of this post.

A lot has been written about the sins of Christian missions and missionaries in the global South, or in the “darker” world, dark in both senses of skin color and as opposed to “light”-----the "light" of modern (Western) “civilization” or that of Christian “salvation” that would pull the “heathens” out of the darkness of their false customs and traditions; I say "or" because the one is always difficult to separate from the other especially after the dawn of secular modernity in the West some centuries ago. Most of this critical scholarship has been carried out by the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist historians of the global South-----the anti-racist intellectuals of the non-Western world. So much so that the Nobel Laureate bishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa who was also, alongside Nelson Mandela and others, on the forefront of the anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements in colonized Africa once said this of the Western (white) missionaries:

“When the white missionaries came to Africa, they all had

the Holy Book (the Bible) in their hands and not much else. To the black Africans

who did not have that Holy Book but who owned everything on the continent----the land, the animals, the resources,

the riches-----the missionaries said: ‘Let us close our eyes and pray to the

Lord.’ We Africans did so; we closed our eyes and we prayed to the Lord. And

when we opened our eyes, we saw that the Africans had the Holy Book in their

hands and nothing else; the white missionaries now had everything that once belonged

to us: the land, the animals, the resources, the riches of the continent.”

I think this is an apt evaluation, given the tainted history and the many ignoble

activities of the Western Christian missionaries in the peripheral Asiatic and

African worlds. The missionary educational institutions, for example, may have

done a lot of good in the colonized lands but one of their main aims was to produce

a clerical class of natives----the ”babu” class----to serve the empire. The

function of this class was clearly described by that champion of colonialism,

the racist Lord McCauley, in his notorious “Minute on Education” of 1835. But just as the wise Tutu pronounced his

verdict as a Christian clergyman-----conveying to the world that he and millions of others like him had embraced the sacred message of an authentic, revealed

religion while identifying the profane and ugly interests that used that original message for worldly material gains as it was being transported to the far-off lands-------let us

also acknowledge, even if we don't go though the process of conversion like Bishop Tutu did, some of the good things that have resulted in our part of the world, thanks to the long

presence of the missionaries there. In short, the fault did not lay with the divinely revealed message of Christianity-----a sister religion of Islam in the monotheistic family of faiths----- but with the imperfect world in which it was received and especially with the ways in which it was, and still is in many places, often preached and propagated by its less-than-perfect followers. Perhaps we should also heed the words of another twentieth century sage, M.K. Gandhi, himself influenced by Christianity (especially by the sermon on the mount) and who once said about it that, “Christianity was a good religion before it went to Europe!”. Just as we Muslims are quick to differentiate between Islam as a revealed religion, as a deen and a sacred worldview, and Muslims as its imperfect followers (as to what they say and do, their words and deeds that often do not live up to the standards and ideals of their religion), it is only fair to accept the same kind of reasoning offered by our Christian neighbors. What the late American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr once said about religion that “Religion is good for good people and bad for bad people”, can be modified to read, “Good people who see the truth, goodness and beauty of religion are always mindful of the consistency of means and ends, while bad people will always abuse religion, will use it instrumentally, as a means to their own evil designs and ends.”

|

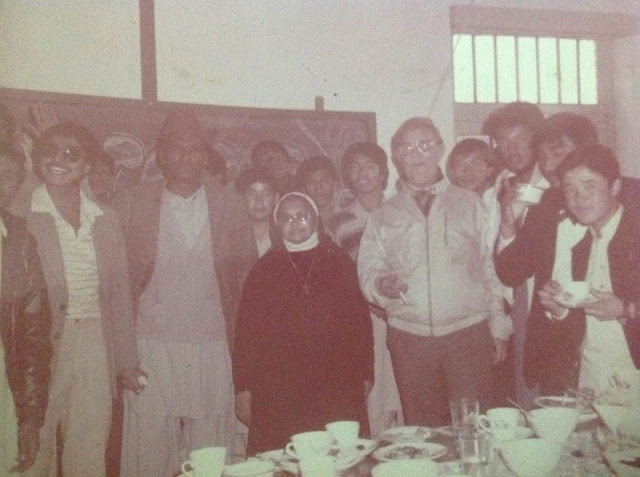

| Fr. Joshua, Sister Cecilia, Sir Sultan and the boys |

|

| The school staff with Sister Cecilia |

|

| Fr. Joshua, Sir Sultan, Imran Achakzai, Shuja Kasi and others |

It was a different time and place, really. Words and concepts like “harassment’, “abuse ”, “violence” and so on had not yet entered the social and pedagogical lexicons. Education had not yet morphed into a mere “service” and students were not pampered and mollycoddled in those days like they are nowadays. Teaching was still a proper vocation, a calling, and not just a "job" then and because of which schools did not over-indulge the students and their hypersensitive, helicopter parents, treating them like spoiled “customers”. In other words, the “customer” was NOT always right then. Teachers were teachers first, and only then “facilitators”, “communicative” or “participant" observers etc. Effective reprimand in those days meant both persuading verbally AND disciplining physically. It was punishment that was realistic and an effective way of initiating the child into the hard realities of that terrible thing called life! After all, it is through pain that we often come to see the authenticity of life, as many sages have said. Great human achievements often come from the love of difficulties and through struggles and the overcoming of hardships. Our unhealthy obsession with convenience and comfort nowadays is the negation of all these time tested principles and virtues and we can clearly see what it has done to us, especially to the young. God knows what hells many of those kids of the 70s and 80s would be in now were it not for those slaps, pinches, those finger twisters and knuckle knocks on the head, caning and even punches and kicks that they used to receive from their teachers! You see, it was the intention behind all that “violence” that mattered most.

|

| Sir Behram |

|

| Moulvi Sahib with principal J.J. Edward |

|

| Mrs. Jawad |

|

| Mrs. Rehana |

Of all the principals that we had, Fr. J.B. Todd was one that needs special mention here. He was someone that I will never forget and I am sure that feeling is shared with me by many of my class-fellows. In fact, our time at Grammar School coincided with the tenures of three principals: Fr. Joshua, Fr. Todd and Sister Cecilia. Fr. John Baptist Todd arrived at Grammar High School in the late 1970s or maybe early 1980s. He was a well-known figure of the Christian community in Pakistan, especially in Karachi and in other big cities in Sindh province. At St. Patrick’s High School Karachi, he was even teacher to the former military-dictator-turned- president Pervez Musharraf in the late 1950s. According to Pervez Musharraf, Todd used to give him a good caning whenever he misbehaved in school. Obviously, Principal Todd did not cane and discipline this particular pupil of his enough, for years later he (Pervaiz Musharraf, the murderous goon, the yet another uniformed dunce!) ended up as a nuisance to the nation, and who is now, and will be forever, remembered as the murderer of a Baloch elder and senior political figure of Balochistan, Nawab Akbar Bugti.

A word about Fr. Todd and his legendary cane. Meticulously dressed in his formal grey suit and with neatly combed hair soaked in a liter or two of the finest hair tonic available then, he would make hourly rounds of the corridors with his trademark flexible cane in hand. Upon seeing a victim, a potential prey, a punished student asked to wait outside the classroom by his teacher for some mischief or bad conduct, Todd’s pace would pick up, become brisk, and an impish smile would appear on his face, an expression that could be interpreted in only one way: “Aha! Gotcha!” But during his time as principal, the school did see many improvements, especially in the disciplinary department and in the overall quality of education. And then tragedy befell him. He was shot in the leg but luckily survived. Suspicion fell on one of our class fellows, a boy named Taufeeq or Tanveer (and I think he was originally from Karachi?). I don’t remember much else about that incident. Soon after that, Todd left and was replaced by Sister Ceclia. After Todd, everything changed; things were never the same again. Having taught, tutored and disciplined thousands of pupils over a period of six decades, Fr. John Baptist Todd-----the man with the cane----left this world on December 4, 2017. RIP.

No mention of Grammar School is complete without recalling

Haji. Haji was the bell guy, the postman, the assistant, the helper, the peon,

the security guy and so on. Always in a waistcoat and with a turban on his

head, this handyman was an institution within an institution; he even lived on

the school premises, in a small house on the far side of the lower playground,

next to the school carpenter’s workshop. The carpenter, whose main job was to repair broken desks and chairs, was another permanent fixture at the school. Already an old man, he was there when I entered Grammar School in 1972 and had not changed a bit when I graduated in 1983. People like him and Haji seemed to be time-resistant! Haji's sidekick, Meeru (or Khairu??), was a different character, mainly because he was of a different generation: younger, ambitious and embodying all the new tastes, desires and values of his generation, many of which were antithetical to the old virtues of which Haji and the carpenter were the prime examples. Of course, I say this now with the benefit of hindsight. On the opposite side of that playground,

across from Haji’s quarters, was the canteen which stood like a large sized

gazebo under the shade of the huge berry tree. That canteen served cream buns,

cream rolls, qeema and aloo patties through the holes on all but one side of

the structure to hordes of rowdy, hungry boys during recess.

|

| Class of '83 |

|

| Class of '83 (Sr. Cambridge students) |

Iftikhar Ahmed used to live on Fatima Jinnah Road and whose house I visited often. His father (uncle?) was a lawyer and my grandfather----and later on my father-----was his business client, if I am not wrong. I think Iftikhar also became a lawyer later on. And there was also another Ejaz, Ejaz Akbar. He was often with Imran (Memon?) and the twins, Athar and Azhar. Imran was also close friends with Mir Javed. I also recall Arshad Ali, the scrawny guy with loads of curly hair, as someone with the sharpest wit and always ready with a humorous quip. Farooq Faiz, the son of a high ranking police officer (SP? DIG?) in the city, was the big guy with hearty laughs. There was also another Farooq (Farooq Ahmed?) who used to live on Patel Road, and was my neighbor for some years when we were also living there. He disappeared just before we entered class 9. I think he moved to some other city with his parents. Some from the batch of 1983 were with me at college and university as well: Amir, Saadullah, Shahid and Dawood. These are some of the sketchy memories of the old days in St. Francis Grammar High, Quetta, a past that I carry around with me in my head, and especially in my heart, and which I try to preserve, however imperfectly, by talking about it, often with old friends and relatives. It's a battle, I know---I hope not a losing one!---a battle against cruel time that never fails to put holes in a man's memory. So, like the rest, I will also just say, "those were the days, my friend those were the days...." as the old song reminds us!

Note: In these musings on the past, I have mentioned many

people, places and events; I have also quoted some of those people. Given what

time does to man, and especially to his memory, it is very likely that I have gotten many things wrong, have omitted certain

names, dates and other important facts or have committed many mistakes in recalling

and writing about things past. I accept the mistakes, take responsibility for the

omissions and the commissions, and offer an apology in advance to all those readers who may feel discomfort by the partially correct or factually incorrect information.

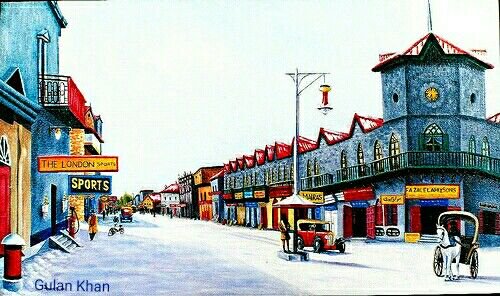

For more on similar topics, please click: Regal Cinema, Qta

Quetta: Then and now