"Tum tata log bilkul isstudy nahi karta hai!" thundered Ms. Nathaniel at Manzoor and Jaffer, two of the several Hazara boys in her class. It was either 1978 or 1979. Years later, after I had graduated from St. Francis' High, whenever I thought of her she reminded me of the many colorful, and at times devilishly conspiratorial, Anglo-Indian characters in the short stories of Saadat Hassan Manto, probably the greatest of short story writers that the Sub-continent has produced. The boys at the receiving end of Sylvia Nathaniel’s trademark rage on that day had not done their homework and were getting a dressing down by her.

The word “tata” was often used for Hazara students at the school and most of the time it was more of a marker than anything else, with not much special meaning, either positive or negative, attached to it or implied by it. As is the case with all such words and labels, the contexts in which it was used-----the people, the relationships, situations, the tone of language used, gestures etc.-----were more important than anything else. Change the context, or the parameters that inform that context, and what was once a term of endearment will quickly become a poisonous insult, a vicious slur on identity, an odious gibe about some weakness or disability and so on. Imagine a man calling a stranger a monkey (bizzo or bandar), a grasshopper (malakh, tidda), a kitten (pisho or billo), a puppy, a gorilla, a pony or even a donkey (khar, kharro or gadha), motay, chotay, thothay and lamboo etc., terms that he uses daily for his children at home. Ever wonder why many best friends use the most abusive of terms for one another? They do it not because one wants to insult or degrade the other, or even the other’s mother or sister in some cases, but because of the great love that they have for each other. Among Hazaras themselves “tata” can mean any of the following: a tradition-bound old man, an elder; an ordinary, no-frills dude; an honest, hard-working fellow who minds his own business and does not care much about the world around him, somewhat like the takari of the Baloch and the Brahvis.

Wikipedia tells me that St. Francis Grammar High School “was established in 1946 to provide education to the elite of Baluchistan and Sindh.” A Roman Catholic missionary school situated on the famous Zarghoon Road (formerly Lytton Road), it is one of the oldest educational institutions of Quetta and has produced many luminaries from a former prime minister to army officers, politicians, writers and ambassadors. There is not much available online on the history of the school and I will not dwell on it since that is not the subject of this blog post anyway. Christian missionary schools were everywhere in Pakistan in those days and there were at least six or seven of them in Quetta at the time we matriculated---in 1983. The “we” here refers to my class-fellows (classmates), some of whom I clearly remember and will introduce them to the readers in the following paragraphs of this post.

A lot has been written about the sins of Christian missions and missionaries in the global South, or in the “darker” world, dark in both senses of skin color and as opposed to “light”-----the "light" of modern (Western) “civilization” or that of Christian “salvation” that would pull the “heathens” out of the darkness of their false customs and traditions; I say "or" because the one is always difficult to separate from the other especially after the dawn of secular modernity in the West some centuries ago. Most of this critical scholarship has been carried out by the anti-colonial and anti-imperialist historians of the global South-----the anti-racist intellectuals of the non-Western world. So much so that the Nobel Laureate bishop Desmond Tutu of South Africa who was also, alongside Nelson Mandela and others, on the forefront of the anti-colonial and anti-apartheid movements in colonized Africa once said this of the Western (white) missionaries:

“When the white missionaries came to Africa, they all had

the Holy Book (the Bible) in their hands and not much else. To the black Africans

who did not have that Holy Book but who owned everything on the continent----the land, the animals, the resources,

the riches-----the missionaries said: ‘Let us close our eyes and pray to the

Lord.’ We Africans did so; we closed our eyes and we prayed to the Lord. And

when we opened our eyes, we saw that the Africans had the Holy Book in their

hands and nothing else; the white missionaries now had everything that once belonged

to us: the land, the animals, the resources, the riches of the continent.”

I think this is an apt evaluation, given the tainted history and the many ignoble

activities of the Western Christian missionaries in the peripheral Asiatic and

African worlds. The missionary educational institutions, for example, may have

done a lot of good in the colonized lands but one of their main aims was to produce

a clerical class of natives----the ”babu” class----to serve the empire. The

function of this class was clearly described by that champion of colonialism,

the racist Lord McCauley, in his notorious “Minute on Education” of 1835. But just as the wise Tutu pronounced his

verdict as a Christian clergyman-----conveying to the world that he and millions of others like him had embraced the sacred message of an authentic, revealed

religion while identifying the profane and ugly interests that used that original message for worldly material gains as it was being transported to the far-off lands-------let us

also acknowledge, even if we don't go though the process of conversion like Bishop Tutu did, some of the good things that have resulted in our part of the world, thanks to the long

presence of the missionaries there. In short, the fault did not lay with the divinely revealed message of Christianity-----a sister religion of Islam in the monotheistic family of faiths----- but with the imperfect world in which it was received and especially with the ways in which it was, and still is in many places, often preached and propagated by its less-than-perfect followers. Perhaps we should also heed the words of another twentieth century sage, M.K. Gandhi, himself influenced by Christianity (especially by the sermon on the mount) and who once said about it that, “Christianity was a good religion before it went to Europe!”. Just as we Muslims are quick to differentiate between Islam as a revealed religion, as a deen and a sacred worldview, and Muslims as its imperfect followers (as to what they say and do, their words and deeds that often do not live up to the standards and ideals of their religion), it is only fair to accept the same kind of reasoning offered by our Christian neighbors. What the late American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr once said about religion that “Religion is good for good people and bad for bad people”, can be modified to read, “Good people who see the truth, goodness and beauty of religion are always mindful of the consistency of means and ends, while bad people will always abuse religion, will use it instrumentally, as a means to their own evil designs and ends.”

|

| Fr. Joshua, Sister Cecilia, Sir Sultan and the boys |

|

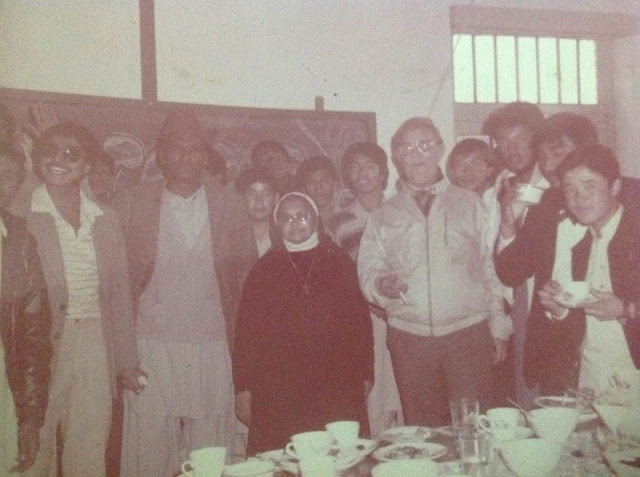

| The school staff with Sister Cecilia |

|

| Fr. Joshua, Sir Sultan, Imran Achakzai, Shuja Kasi and others |

It was a different time and place, really. Words and concepts like “harassment’, “abuse ”, “violence” and so on had not yet entered the social and pedagogical lexicons. Education had not yet morphed into a mere “service” and students were not pampered and mollycoddled in those days like they are nowadays. Teaching was still a proper vocation, a calling, and not just a "job" then and because of which schools did not over-indulge the students and their hypersensitive, helicopter parents, treating them like spoiled “customers”. In other words, the “customer” was NOT always right then. Teachers were teachers first, and only then “facilitators”, “communicative” or “participant" observers etc. Effective reprimand in those days meant both persuading verbally AND disciplining physically. It was punishment that was realistic and an effective way of initiating the child into the hard realities of that terrible thing called life! After all, it is through pain that we often come to see the authenticity of life, as many sages have said. Great human achievements often come from the love of difficulties and through struggles and the overcoming of hardships. Our unhealthy obsession with convenience and comfort nowadays is the negation of all these time tested principles and virtues and we can clearly see what it has done to us, especially to the young. God knows what hells many of those kids of the 70s and 80s would be in now were it not for those slaps, pinches, those finger twisters and knuckle knocks on the head, caning and even punches and kicks that they used to receive from their teachers! You see, it was the intention behind all that “violence” that mattered most.

|

| Sir Behram |

|

| Moulvi Sahib with principal J.J. Edward |

|

| Mrs. Jawad |

|

| Mrs. Rehana |

Of all the principals that we had, Fr. J.B. Todd was one that needs special mention here. He was someone that I will never forget and I am sure that feeling is shared with me by many of my class-fellows. In fact, our time at Grammar School coincided with the tenures of three principals: Fr. Joshua, Fr. Todd and Sister Cecilia. Fr. John Baptist Todd arrived at Grammar High School in the late 1970s or maybe early 1980s. He was a well-known figure of the Christian community in Pakistan, especially in Karachi and in other big cities in Sindh province. At St. Patrick’s High School Karachi, he was even teacher to the former military-dictator-turned- president Pervez Musharraf in the late 1950s. According to Pervez Musharraf, Todd used to give him a good caning whenever he misbehaved in school. Obviously, Principal Todd did not cane and discipline this particular pupil of his enough, for years later he (Pervaiz Musharraf, the murderous goon, the yet another uniformed dunce!) ended up as a nuisance to the nation, and who is now, and will be forever, remembered as the murderer of a Baloch elder and senior political figure of Balochistan, Nawab Akbar Bugti.

A word about Fr. Todd and his legendary cane. Meticulously dressed in his formal grey suit and with neatly combed hair soaked in a liter or two of the finest hair tonic available then, he would make hourly rounds of the corridors with his trademark flexible cane in hand. Upon seeing a victim, a potential prey, a punished student asked to wait outside the classroom by his teacher for some mischief or bad conduct, Todd’s pace would pick up, become brisk, and an impish smile would appear on his face, an expression that could be interpreted in only one way: “Aha! Gotcha!” But during his time as principal, the school did see many improvements, especially in the disciplinary department and in the overall quality of education. And then tragedy befell him. He was shot in the leg but luckily survived. Suspicion fell on one of our class fellows, a boy named Taufeeq or Tanveer (and I think he was originally from Karachi?). I don’t remember much else about that incident. Soon after that, Todd left and was replaced by Sister Ceclia. After Todd, everything changed; things were never the same again. Having taught, tutored and disciplined thousands of pupils over a period of six decades, Fr. John Baptist Todd-----the man with the cane----left this world on December 4, 2017. RIP.

No mention of Grammar School is complete without recalling

Haji. Haji was the bell guy, the postman, the assistant, the helper, the peon,

the security guy and so on. Always in a waistcoat and with a turban on his

head, this handyman was an institution within an institution; he even lived on

the school premises, in a small house on the far side of the lower playground,

next to the school carpenter’s workshop. The carpenter, whose main job was to repair broken desks and chairs, was another permanent fixture at the school. Already an old man, he was there when I entered Grammar School in 1972 and had not changed a bit when I graduated in 1983. People like him and Haji seemed to be time-resistant! Haji's sidekick, Meeru (or Khairu??), was a different character, mainly because he was of a different generation: younger, ambitious and embodying all the new tastes, desires and values of his generation, many of which were antithetical to the old virtues of which Haji and the carpenter were the prime examples. Of course, I say this now with the benefit of hindsight. On the opposite side of that playground,

across from Haji’s quarters, was the canteen which stood like a large sized

gazebo under the shade of the huge berry tree. That canteen served cream buns,

cream rolls, qeema and aloo patties through the holes on all but one side of

the structure to hordes of rowdy, hungry boys during recess.

|

| Class of '83 |

|

| Class of '83 (Sr. Cambridge students) |

Iftikhar Ahmed used to live on Fatima Jinnah Road and whose house I visited often. His father (uncle?) was a lawyer and my grandfather----and later on my father-----was his business client, if I am not wrong. I think Iftikhar also became a lawyer later on. And there was also another Ejaz, Ejaz Akbar. He was often with Imran (Memon?) and the twins, Athar and Azhar. Imran was also close friends with Mir Javed. I also recall Arshad Ali, the scrawny guy with loads of curly hair, as someone with the sharpest wit and always ready with a humorous quip. Farooq Faiz, the son of a high ranking police officer (SP? DIG?) in the city, was the big guy with hearty laughs. There was also another Farooq (Farooq Ahmed?) who used to live on Patel Road, and was my neighbor for some years when we were also living there. He disappeared just before we entered class 9. I think he moved to some other city with his parents. Some from the batch of 1983 were with me at college and university as well: Amir, Saadullah, Shahid and Dawood. These are some of the sketchy memories of the old days in St. Francis Grammar High, Quetta, a past that I carry around with me in my head, and especially in my heart, and which I try to preserve, however imperfectly, by talking about it, often with old friends and relatives. It's a battle, I know---I hope not a losing one!---a battle against cruel time that never fails to put holes in a man's memory. So, like the rest, I will also just say, "those were the days, my friend those were the days...." as the old song reminds us!

Note: In these musings on the past, I have mentioned many

people, places and events; I have also quoted some of those people. Given what

time does to man, and especially to his memory, it is very likely that I have gotten many things wrong, have omitted certain

names, dates and other important facts or have committed many mistakes in recalling

and writing about things past. I accept the mistakes, take responsibility for the

omissions and the commissions, and offer an apology in advance to all those readers who may feel discomfort by the partially correct or factually incorrect information.

For more on similar topics, please click: Regal Cinema, Qta

Quetta: Then and now

Salam Asghar remember me Arshad Zubair. This is nice endeavour you made to make us remember who we are and where we belong from. Warm regards.

ReplyDeleteHi....Asghar Ali

ReplyDeleteThis is Suleman Lodhi, excellent work from you, I would suggest that each class fellow or school fellow of us may contribute an incident from school time with dates and then we can combine it together in a wiki document or blog and the history will re-live its self

Beautifully discibed gone back to my school days seems yesterday

DeleteJehangir jaffar

Hi,Asghar it's me Waseem Baran,commendable effort it really took me in the realm of memories and I got my self lost in the past.Bundles of thanks.

ReplyDeleteSweetheart Asghar

ReplyDeleteToday you throw me back in my golden days miss you all

And i just finished call from amir Raza we were talking on your blog n remembering good old days

Miss you sweetheart

Mir javed

Salam dear friends, class of ’83 Grammarians. For some strange reasons this blogger software was not accepting my reply to your generous comments in this comments section so I added this same acknowledgement to the post earlier, which I have removed now.

ReplyDeleteThank you for the kind words and all the comments. It makes me happy to hear from so many of you, either directly through your comments here or through the large number of hits that the blog has received in just a day. I am sorry for not mentioning everybody. Please blame my poor memory for that; it was not intentional, as I have also said in my note at the end of the post. Please share with other friends from school that you are in touch with since I am not on the social media. Share especially with your children so that they can get a glimpse of how things used to be back then. More to come in the near future, Inshallah.

Dear Sir, this is an excellent work and great effort. I belong to the class of 88' and would like to share that our school was established in 1936 and have a list of all principals, shared by one of our 'class-fellows'.

ReplyDeleteEid Mubarak!

ReplyDeleteHello, there. Outstanding blog! Your writing is so colourful and detailed that for a while, I thought that I was reading a novel, what with vivid description of things and events in your narrative. Superb story-telling and a flawless use of the English language. For sure, your English teacher (whom you described on here) influenced your style of writing in many ways.

I am one strange fellow from Canada who is learning about Pakistan and the Pakistani people. One YouTube travel show to Baluchistan led me to search about your school (when it appeared in one of the comments) and, voila, landed on your page!

Hope to connect with you. I would like to learn more about your country and your people. My e-mail is on here.

Best regards from Vancouver.

I was admitted in 1983 by Sister Cecilia, I had this Badge.

ReplyDeleteGoing further back in time, I attended St Francis Grammar from Class 2 in 1963 and passed Matric 1972. Teachers included Sir Qadeer (History), Sir Kareem (Urdu). Cambridge line teachers included the stylish Ms. Kaneez Fatima and her equally stylish brother (Zaidi?). Ms Gul Walter in Class 8 and her sister in Class 7.

ReplyDeleteGood memories, but unpleasant the months after graduation. School had tradition to offer two academic gold medals to the Matric graduates during the “Sports” day in October. One for highest total score and one for highest in Science from Grammar school. I earned both but awarded neither. Only credible reason I was Bengali, and Bangladesh had broken off from Pakistan less than a year earlier. Even after 48/years, the memory stings when I think about it. Lesson is do not withhold what has been earned. Zak, Tennessee, USA

Dear ZAK, Thank you for leaving your comments here, and my apologies for this late response. As I have said in the introductory post of this blogsite, the blog is just a Quettawaal's musings (and at times rantings!) about what the little town once was and what it has become, and fast becoming, unfortunately. What happened in 1971 will always remain a dark, if not the darkest, chapter in the short but sickeningly tragic history of the country. What was done to the Bengalis then----systematic violence, ethnic cleansing----is still being carried out (although on a different scale) against other regional, ethno-linguistic groups who do not subscribe to the dominant consciousness, or who do not share the worldview of the country's genocidal ruling elites (especially its uniformed cadres). The truly tragic thing is that the majority of Pakistanis have yet to become aware of the existence of the Hamoodur Rehman Commission Report that details, even if partially and with bias, the crimes of the ruling elites of Pakistan at the time of creation of Bangladesh, let alone read it and reflect upon it! That is how profoundly bamboozled the masses are, thanks mostly to the rotten, jingoistic education system and the obscene and obscenely controlled mass media. This being the case, how can one even think of atonement for the terrible violence of 1971? There are, of course, individuals and groups here and there, especially in the smaller provinces like Balochistan and KP, who feel the pain of the Bengalis and what they went thorough in the 70s. Like the aware Bengalis then, these are the peripheral people who have seen through the 70 year old toxic system of ruthless exploitation, of loot and plunder of the marginalized and powerless by the bloodsucking mafias of the Center, a cabal of seasoned criminals that is like one huge killer squid.

Delete