|

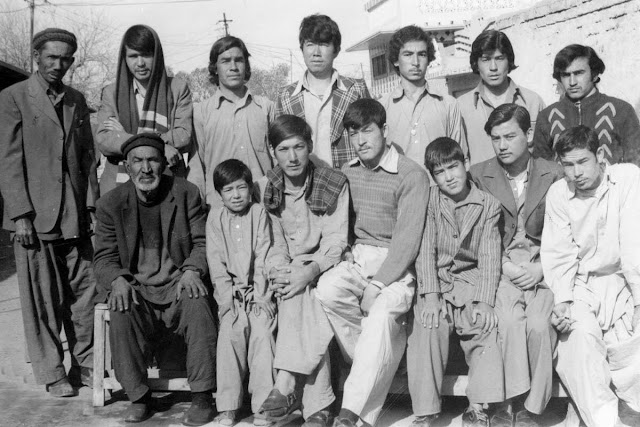

| Faqir Jango of Hussain Abad, Quetta. |

John Gray

"We have too many things, and too little gratitude."

Abdal Hakim Murad

Note: Short video on Hussainabad at the end.

Haider Surkhai. Faqir Jango. Shaukat Cowboy. Eechak. Seyyed Tawoos Agha. Babay Patayn. And so on. All these names are of the people whom we identified as our own, as the people of Hussain Abad, a neighorhood where we grew up in the 1970s and 1980s. Hussain Abad is a mostly Hazara mohalla (neighborhood) off the main Toghi Road in Quetta. I am not sure about the origin of the name; maybe it was named after the first person who set camp there; since the Hazaras belong to the Shia tradition of Islam, it is more likely that the mohalla was named after the third Shia Imam Hussain (AS), the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). Wallahu alam. God knows better. In this blog, I will reflect upon the old days in Hussain Abad---1970s and 1980s---some of its well-known residents and the customs and mores which defined the community then.

The residents of Hussain Abad were then commonly known by

the Hazaras of other mohallas, especially by the slick Nichariites and the brash (or let's say blunt, brutally honest) Seyyed Abadis,

as the “Shash Maina” which literally translates into “Six Monthers” or “Six month

old”. For those readers of this blog who are not well acquainted with the

Hazaras of Quetta and their ways, this appellation was both an honorific and a somewhat

derogatory designation at the same time. The Hussain Abadis, having arrived

into this world from the wombs of their mothers three months earlier than others

of the species (hence the sobriquet “six monthers”!), were admired, or envied, for their

precociousness, wit and wisdom, resourcefulness and other such qualities that usually

define the better segments of a community. At the same time, and rather

paradoxically, they were also the target of caustic taunts---especially of the irreverent Seyyed Abadis---for having not advanced beyond the age of

six months, postpartum (post-birth)! In other words, they were often accused of

immaturity. Those TNT-loaded barbs were especially lobbed at them by the Seyyed

Abadi fans at the football (soccer) matches between the two teams during

the All Hazara Football Championships often held in dry Quetta summers. Local

elections for the provincial legislative assembly were the other such occasions

for such a belligerent display of communal rivalry.Abdal Hakim Murad

Note: Short video on Hussainabad at the end.

Haider Surkhai. Faqir Jango. Shaukat Cowboy. Eechak. Seyyed Tawoos Agha. Babay Patayn. And so on. All these names are of the people whom we identified as our own, as the people of Hussain Abad, a neighorhood where we grew up in the 1970s and 1980s. Hussain Abad is a mostly Hazara mohalla (neighborhood) off the main Toghi Road in Quetta. I am not sure about the origin of the name; maybe it was named after the first person who set camp there; since the Hazaras belong to the Shia tradition of Islam, it is more likely that the mohalla was named after the third Shia Imam Hussain (AS), the grandson of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh). Wallahu alam. God knows better. In this blog, I will reflect upon the old days in Hussain Abad---1970s and 1980s---some of its well-known residents and the customs and mores which defined the community then.

|

| Hussain Abadis at Hanna Lake, Quetta, mid 1970s. |

On a recent visit to Quetta, I went to check on the old

mohalla of Hussain Abad, especially the street that we used to live in. Once

there, I was totally lost: almost nothing of the old street could be seen! I

had difficulty orienting myself and tried hard to locate the exact location where

once stood the old house with the huge mulberry (shahthooth) tree---our house.

Gone were the small wooden doors with sun-beaten dried paint that we children used

to strip off the door surfaces mischievously. Those small doors with squeaky hinges and rusting bolt-type locks with chain latches that doubled as knocking devices were almost

always half open; simple yet elegant, they never failed to remind one of the organic ("wood is always alive!" as someone has said) and unpretentious nature of not only the structures that they were meant to gate and protect,

but also of the people who inhabited those quarters. In them one could see and feel what the Japanese call wabi-sabi. In place of them now stood

wide metal gates fitted with high security prison grade remote operated locks and

flanked by reinforced concrete walls into which the hinges that supported the thick,

heavy gates sank deeply, as if trying to impress upon the mortal observer that

both the structures and their residents were there to stay indefinitely, as in death-defying indefinitely.

Forever! I just stood there, in front of one of those cold, lifeless monstrosities

for a long time, thinking about the old times. In exact contrast to what

occupied those spaces once, everything now looked so…inorganic, so

un-charming, so arrogant, gaudy, nay, ugly!

As with the buildings, so with the people. Looking strangely,

suspiciously, at me as I walked past them---still somewhat lost and confused---the

cold, unfamiliar faces seemed equally unfamiliar to each other as well. The fruits of development, progress, or "taraqqee", I thought. Hence the booming market for NGOs and their armies of "community developers"! As I turned the corner to get back on the main Yazdan Khan Road, my eyes suddenly caught sight of an abnormally thin man with an equally emaciated face half of which was covered with a scraggly beard. He was just standing there, almost motionless. He was clad in all white, head covered with a black and white keffiyeh, of the type that always reminds one of the great Palestinian freedom fighter, Yasser Arafat. His eyes that seemed to have lost their shine decades ago met mine and that brief moment during which we locked eyes seemed like a very long time: decades of memories quickly rolled down in front of my eyes, in that familiar yet strange space between us. Still looking at him, I halted once and then slowly moved closer to him until I was standing at an arm’s length from him. I knew the man. Yes. I had always known him. “Recognize me?”, I asked him. A few seconds passed. Nothing. His eyes were still searching for something. Finally, he extended his right hand to me and smiled, more with his eyes than with his mouth. I took his hand and told him who I was. He nodded once, twice and then doing it continuously, he squeezed my hand hard in his as the smile spread all over his face, the shine returning to his eyes. “Yes, I remember you. Yes, I do” he kept saying. This was Ahmed Ali, son of the late Haji (Mullah) Ghulam Ali who was a meticulous man, a rather brutal disciplinarian and a great teacher of Islamic subjects to the boys and girls of Hussain Abad. After a very long, long time, I had met Ahmed Ali, or Ahmed qun quni of Hussain Abad, as he was known to all of us.

|

| The community, early 1970s |

|

| Hussain Abadi "Shash Mainas" in winter, early 1980s. |

|

| Haider Ali marhoom (Khuda biyamurza, RIP). Hussain Abad in the late 1970s. |

But if there is one personality who is justifiably qualified to be identified with Hussain Abad, to be the face of Hussain Abad so to speak, I would say that honor should go to Faqir Jango. There is so much to say about this doyen of Hussain Abad (at least to three generations of its residents!), but what brings to the mind of any Hussain Abadi who hears his name is a pair of sunglasses. And not just any sunglasses but a pair of classic RayBans: to say Faqir Jango is to visualize a pair of original Raybans Aviator with dark tinted glasses. This man, alive and kicking as I write these lines, with his unique communication style and his limitless store of witty anecdotes and original jokes, had the uncanny ability to engage people of different age-groups in hours long sometimes informative and often entertaining conversations. Except for the terribly freezing rainy-snowy winter days, on a typical evening in the decades of 70s and 80s in Hussain Abad, it would be impossible to miss the sight of Jango telling his jokes or narrating some anecdote, surrounded by boys and men of all ages. The usual venue for such live information sessions and verbal performances would be the street corner, in front of babay Maqsood’s general store. Years later, after I had left Quetta and after I had read enough about and by (via his illustrious student Plato or Aflatun) the wise old man of Greece, Socrates, I often thought of Faqir Jango and his captivated audience at that street corner in Hussain Abad. Definitely no Socrates to his captured flock, Faqir Jango had the same power to cast a spell, and the charm, too, of the Athenian sage.

(to be continued…)

Hussainabad: The Video

-------------------

For the interested reader, more about the yesteryears,

Khuda biamurza

ReplyDeleteExact description of shash mainas :) as myself is one of them.Took me back to my childhood and to the streets Hussain abad while I was reading those lines :) Made me smile and brought tear in my eyes. Yad shi bakhair. Marhomeen ra Khuda biyamurza wa una ki baqi ya jani jori bida.

ReplyDeleteSamad az Stavanger Norway

Those were the days my friend 😀

ReplyDeleteHad a good time while reading this blogg.constantly smiled thinking back.hopefully Will be hearing/Reading more from you about pasta days. Good luck with everything😀

Zulfo from Norway (Haugesund)

Lala i admire the way u cover and portray the people and time in a fascinating way which evokes the old memories and those people which u described. As a Hajiabadi adjecent to Hussainabad we were also called Shashmaina by Syedabadiya like my uncle Shaukat Awoo now resides in Hamburg, till now when ever we speak he calls me o Shashmaina kujayi. Gr8 work Lala, keep it up. Ahsan.

ReplyDeleteI can't access the video. Really thought it would take me back to my childhood. Please let me know if there's some other way to access it. Thanks.

ReplyDeleteHello. I took down the video because of Youtube copyright issues. It was the Bollywood Sholay song, "Ye dosti...". Sorry for the inconvenience. If you send me your email address I can send you the video .

Delete