|

| Toyota Corona Mark II (1974) |

(Note: short video at the end)

"A car is like a mother-in-law - if you let it, it will rule your life." Jaime Lerner

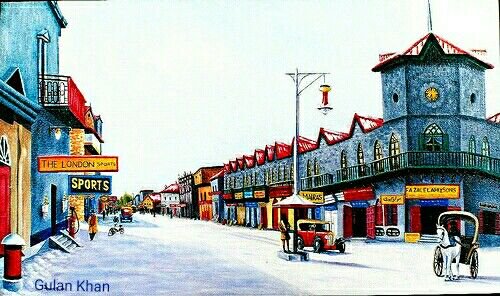

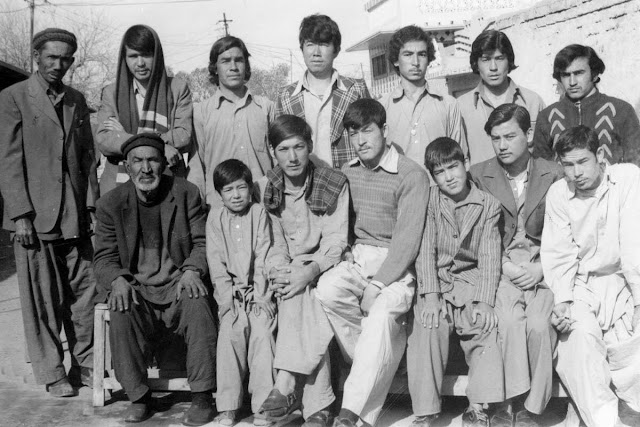

“Pardey mein rehne do, parda na uttawo” sang Asha Bhosle through the dashboard speaker connected to the portable car vinyl player as we, my uncle Samad Ali driving, cruised along Zamzama lane (Chiltan road?) in the direction of Pani Taqseem in the cantonment area of Quetta City. I think it was the spring of 1971. The car we were in was an off-white 1968 Toyota Corona. This is one of the few memories that I have of my late uncle, a pilot in the first fighter squadron---the No. 9---of The Pakistan Air Force, and especially of his car. I was barely five then! And this was also the last time I was with him: he was martyred a few months later, in the Indo-Pakistan war of 1971. His Lockheed F-104 Starfighter was shot down in Indian airspace in the middle of his eleventh mission. That story I will explore in a future blog post, Inshallah (God willing). For now, let’s turn to the cars of the old days, to the decades of 1970s and 1980s.

Two Japanese brands ruled the car landscape of Quetta, or of

Pakistan in general, during the 70s and part of the 80s, too: Toyota and

Datsun. The latter had not yet evolved, or morphed, into Nissan. That happened

towards the end of 1980s or early 1990s, as we also witnessed another Japanese

manufacturing giant, the home appliance maker National, transform itself into

Panasonic. There was, of course, Mazda, the third big automobile maker from

Japan. Suzuki also had some presence, mostly in the form of its ubiquitous

mini-truck, the small Carry “pick-up” which came in one color only, white. Japanese

truck manufacturers like Hino and Isuzu had not yet entered the Pakistani

market which was dominated by Bedford Lorries, the commercial vehicle wing of

the British manufacturer Vauxhall Motors. Nobody used the brand name for the

lorries; they were universally called “Rockets” by their local owners and

drivers.

My first car ride was not in my uncle’s 1968 Toyota. It was

in my grandfather’s 1958 Chevrolet Impala. A pistachio-green Chevy with huge whitewall

tires and tons of chrome, it looked so huge to us kids. We loved it because it

was perfect for our game of teelo teelo, a local version of hide-and-seek. The

car did not so much offer nooks and crannies to hide in, but was perfect for

running around, escaping from and tiring down the seeker in the hide-and-run-when-found

game. And then there was the old Willys Jeep which my grandfather and his

younger brother used to drive to the coal mines in Mach-Bolan. Both were in the coal business.

The Datsun Sunny, especially the humpy 120Y, was another mule of a car that equally resisted visits to the garage and the gas station. Although not good in the design department, it was simply the best car when it came to fuel economy and durability, and that is why the B110 Sunny 1200 model (1970-73) earned the label “Karachi Taxi”. Exclusively in black with yellow rooftop, they were ubiquitous on the roads of Karachi. Even now, they can be seen in some parts of the port city.

The Toyota to rival the Sunny in toughness and durability,

if not in fuel economy, was the Corona Mark 1 (1973). Slightly bigger in size,

this car also lasted forever. They were still around, as late as 2007, when I

visited Quetta. The most popular color was beige. Arbab Asif Hazara (a NAP

politician) and my school friend Ejaz ul Hassan’s uncle in Tel Gudam (a Toghi

Road mohalla or neighborhood) were proud owners of this hardy perennial machine. With simple, solid body lines,

this car had a beautiful front grille and it looked muscular when equipped wide

radial tires.

The Mazda cars in the Quetta of '70s were not so much about

fuel economy as about design and comfort. Mazda had a good reputation for

suspension and design. It made some of the sexiest cars then. The Luce 1500 and

1800 (also called Mazda DeLuxe) were real beauties of the day. The sleekness in

car design that became synonymous with brand Mazda some years later, thanks

mostly to its legendary sports car the RX-7, could already be seen in the Luce

models. The proportions, the body lines, the cool grille and headlamps, and the

slim Alfa Romeo style tail lights—everything was perfect about the Luce. And to

top it all, it had the most beautiful wood paneled dashboard that I have ever

seen in a Japanese car. The car sat low, lower than all the other Japanese

models available then. I had a special affection for the metallic blue Luce 1800

that my uncle Sadiq owned. We would spend hours on Sundays washing and waxing

it with the finest car wax , the softest of yellow waxing cloth in combination

with silky white sootar (soft cotton waste from the textile mills) that were

sold at the auto spare parts shops on Wafa Road. Every time I see an RX-7 here in Japan (where

I live now), a Mazda icon that I have always loved, I cannot help thinking

about the Mazda Luce in the Quetta of ‘70s.Mazda also made some really tough cars to match the Datsuns and the Toyotas. One such car was the Mazda 808 Station Wagon, the little sibling of the more powerful Mazda RX3 Sports Wagon, another beautiful Mazda (the RX3, that is). Nobody is in a better position to confirm that claim than my childhood friend Sikander, whose father owned one. It was a red wagon and if I remember correctly, the car stayed with the family for more than a decade, maybe two decades. Sikander used to race around that car like some stunt car driver, but always out of sight of his observant father. Sikander was an excellent driver, no doubt about that, but he was rather harsh on that car. Any other car would have long ended up as scrap metal in the city's only kabari (Quetta's main scrap metal market) but that red Mazda survived Sikander’s brutalities with grace. He could not be blamed too much, anyway. Movies like The Moving Violation, and before that, The Italian Job and later the hit David Hasselhoff TV series, Knight Rider, were all the rage then. (All Fast and Furious movie fans reading this, you have got to watch that movie, The Moving Violation. Guys, that’s where it all started!)

Now let me come to the machine that I think defined the ‘70s

of Quetta and its real car enthusiasts. I think none of the cars mentioned so

far, not even the much admired Luce/Deluxe, can ever be compared in any

meaningful sense with this classic. In fact, it would be outright disrespectful

to talk about this car in the same breath as all the others that were around

then. And the car is…the Toyota Mark II (1974). It was actually Toyota Corona Mark II but the

“Corona” bit was always left out: Mark II, just like that. Now, think for a moment of a

Porsche 911 Turbo, a Lamborghini Aventador, a Ferrari Enzo or F40, or even of a McLaren, a

Koenigsegg or a Bugatti, imagine what these cars mean to their admirers and owners, and you can get an idea of what the Mark II meant to

its owners and admirers then. This is not an exaggeration at all; I am saying all this from experience, real lived experiences, if I may say that to make my point about the Mark II.

My uncle Sikander (or maybe it was his friend) actually drove one all the way

from Germany to Quetta! He just wanted his Toyota Mark II in Quetta, not any

German car which he could have easily bought and driven to Pakistan upon his eventual

return from that European technological powerhouse best known for its superb cars.

That’s the kind of following the car had then. The car meant power and comfort,

first and foremost. It was a heavy, muscular gas guzzler, and it definitely had

the lines and the elegant form to rival any other car in those departments then.

The interior was plush: all leather and wood paneling in the GL and coupe models.

The coupe, with the wide Good Year radials with white lettering, was a real killer.

It may well be one of the most beautiful two-door cars to have come out of

Japan, as some car connoisseurs have also claimed.

The 1980s arrived with the beautiful Toyota Corolla 1980, a

car that looked like the re-incarnation of the ‘68 Corona, with four headlamps

and a plain grille. With it was introduced such goodies as power windows and

hydraulic steering and bumpers. A year later, the Corolla 1981 was released

with tiny, square headlamps. It was an ugly, Ladaesque thing: a stupid attempt

to improve upon the 1980 model. The makers soon realized their blunder and a year later released the Corolla 1982 with wide, rectangular head lamps and beautiful

tail lights. That model was a big success. It was also the 1980s when Honda

properly launched its line of cars in Pakistan, or maybe they arrived earlier

but that is when they started to become visible In Quetta, especially the Civic

and the Accord models. Both went on to become success stories in Pakistan, just

like elsewhere in the world. The Civic continues to compete with Corolla for

market share in the compact car category in Pakistan. Honda cars may have been

success stories everywhere, but for yours truly they have no appeal. I have

never liked the brand. I guess part of the reason is because they were not

around when we were growing up in the Quetta of 1970s and so I cannot connect

with the cars in any meaningful way, the way I can with Toyotas and Datsuns

(Nissan). The company’s motorcycles are another matter, though: I love Honda bikes.

Another important thing that happened in the 1980s was the launch of diesel

engine SUVs, especially the Mitsubishi Pajero (always called "Pijaro" in

Pakistan) and the Toyota Land Cruiser. That story is for another day.

I have skipped over two Toyota models of the 1970s: The ’74

and the 1978-79 Corollas. The story of the ‘74 will need a full, separate blog

post. Called by different names---some good and some rather obscene that cannot

be mentioned on this PG rated blog, but all implying durability and good

re-sale value---it was not just a car, but an institution in its own right. The

1978-79 Corollas were in an altogether different class. They were the exact

opposite of the ’74 Corolla. With poor re-sale value, they were---especially the

’79--- the cars of choice for car junkies, the fanatics who are deep into

customization and remodeling. With minimal body fittings and big, wide tires

with white lettering (always called radial tires by the locals) the plain looking ’79

could be transformed into a mean-looking machine. The ’79 Corolla had a stylish grille.

Cars used to be simple then. They were, first and foremost,

mechanical contraptions, devoid of all the “smart” electronic aids and wizardry

that one sees in today’s cars. The only electronics under the hood and inside

the cabin were the ignition system, lighting and things like radio, heating (no

A/C), wiper and indicator switches etc. all dependent on one 12V hard rubber lead

plate battery. No EFIs, just the old style carburetors mechanically connected

to the camshaft and the governors that controlled the air-fuel ratio for

desired combustion rates. Concepts like “hydraulic”

and “power”—power this and hydraulic that---had not yet entered the vocabulary

of car sellers and buyers. It was usually the radio, the upholstery, and in

some cases the car vinyl player, that would turn a standard, no-frills model

into a GL which stood for grand luxury. In short, cars were cars first than

anything else; they were definitely not your personal drawing room stuffed with

all the entertainment gizmos. And driving used to be a real experience of

man-machine interface---real synergy, pure symbiosis----requiring different

skills, physical strength and a full-time, 360 degree awareness of what was

going on around you, all with the help of a tiny rear view and two fixed side view mirrors. Sorry, no rear view monitors or navigation system then.

James May, the co-presenter---alongside the loud-mouthed Jeremy Clarkson---of the well-known TV motoring show Top Gear once said, “a car isn’t a classic just because it’s old. To be a classic, a car has to tell us something of its time”. And tell they did a lot, those Quetta cars of the 1970s---the 120Y, the Luce, the 70s Corollas, the Mark I and the Mark II. Built to last, and not planned for obsolescence, all of them embodied the ethos of their time, which could be seen in their simple yet elegant designs, in their durability and individuality, in the craftsmanship that had gone into their making and in the rewarding experiences of driving (minus the cruise control) on the open roads of the time that they offered to car enthusiasts. No wonder, they are still around and much loved!

James May, the co-presenter---alongside the loud-mouthed Jeremy Clarkson---of the well-known TV motoring show Top Gear once said, “a car isn’t a classic just because it’s old. To be a classic, a car has to tell us something of its time”. And tell they did a lot, those Quetta cars of the 1970s---the 120Y, the Luce, the 70s Corollas, the Mark I and the Mark II. Built to last, and not planned for obsolescence, all of them embodied the ethos of their time, which could be seen in their simple yet elegant designs, in their durability and individuality, in the craftsmanship that had gone into their making and in the rewarding experiences of driving (minus the cruise control) on the open roads of the time that they offered to car enthusiasts. No wonder, they are still around and much loved!

For more, please click:

|

| Dervaish's Quetta Youtube Channel (Click) |