“…God citeth symbols

for men to remember.” (Qur’an, 14:24-25)

"We cannot pretend to culture until by the phrase 'standard of living' we come to mean a qualitative standard...Modern education is designed to fit us to take our place in the counting-house and at the chain-belt; a real culture breeds a race of men able to ask, 'What kind of work is worth doing?'"

Ananda K. Coomaraswamy

"Value intensiveness more than extensiveness. Perfection consists in quality, not quantity. Everything very good has always been brief and scarce; abundance is discreditable. Even among people, giants are usually the true dwarves. Some value books for their sheer size, as if they were written to exercise our arms not our wits. Extension alone can never rise above mediocrity, and the misfortune of all-embracing individuals is that, wanting to deal with everything, they deal with nothing. Intensity leads to distinction, and to heroic distinction if the matter is sublime."

The worldly wisdom of Baltasar Gracian

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

There was a time when

people in traditional societies said so less and meant so much. It was a time

when things did not even have proper names, yet they were rich with purpose and

overflowing with meaning. Now, men and women say so much, chatter

non-stop---both online and offline--- and all that they say mean so little, if

anything at all! Everything now has

explicit names, elaborate definitions, colorful labels and explanations, but

lack meaning and purpose.

People did good acts

without running around like some wound-up robot advertising their noble acts, shamelessly

indulging in self-promotion and self-marketing. Virtues like charity were more

practiced than displayed, praised or talked about: a kind act was just done, always

for Allah’s sake, and then forgotten by the benefactor, or “thrown away into

the river” (neki karr, darya mein phenk). When it came to virtuous acts like

helping the poor and the needy, such was the quality of character of both the high

and the low, the khawas as well as the awam, that the left hand was not

supposed to know what the right hand was doing or had done, whom it had helped

or had provided succor. Others’ faults and weaknesses were rarely discussed or

criticized in public: disagreement, disapproval and reprimand were often subtle

and indirect. Compare that to what today's uber-literate and "educated" people do on Facebook, Tiktok and Twitter etc. nowadays!

The time was when

people, ordinary as well as the elite, serf as well as lord, had eyes and

intelligences that could see the “picture that is not in the colors”. People

who could neither read nor write---the illiterate or what we moderns

slightingly refer to as “ignorant” (jahil and ganwaar)--- but who were often

profound possessors and practitioners of insight, foresight and wisdom. Yes, they were illiterate as

measured against today’s criteria of formal literacy and education, but they could

tell month-long stories of wisdom and recite epic poems from heart. Above all, there was

self-effacement and humility. People were certain more about what they did not

know, their ignorance, than about what they could claim as knowledge. And when

they did make such claims, they would often complement them with Wallahu Alam (God knows best).

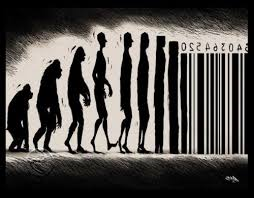

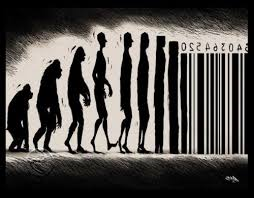

Now, we, the (post-)

modern “chattering shadows of shadows” as the late poet Kathleen Raine once put

it, don’t even see the colors in vividly painted pictures, let alone recite

long poems or tell captivating, interesting stories. We are the progressive, “information rich” and

knowledgeable people, over-confident about all and everything under the sky,

and never failing to look down upon the people and the ways of the past, that "backward" time and place from which we have emerged, out of which darkness we have "evolved" into light all starry-eyed. We cheerily tell ourselves that we

are more “advanced” and “developed” than our predecessors. But, in fact, we are the overly literate and

educated holograms, unreal and empty images constantly gossiping and telling

inane tales that are often ‘full of sound and fury, signifying nothing’!

One reason for this

state of affairs is the loss of symbolism in our languages which is itself a

reflection of our dull, simplistic thought patterns. Whatever else they were or

were not, traditional languages were always symbolic. Symbolic language meant

that its users were aware of and in communication with something higher than

themselves, since the main function of a symbol is to connect the lower to the

higher. A traditional/religious symbol helps us climb up the ladder of meaning,

of purpose; it helps us transcend the mundane and the trivial, this

going-beyond being the main purpose, the raison d’etre, of life in traditional

cultures. Symbols are like memory pills in that they remind man (insaan) of

what he has forgotten (his ghaflah, and this ghaflah being a major failing of a

Muslim). Those forgotten things are the real things amidst whose reflections or

shadows we live out our lives in this world, somewhat like the cave dwellers in

the allegory of Plato. Symbols are like keys that help us open doors to divine

mysteries that otherwise remain locked and inaccessible. Important to remember

is that in the world of symbolism, height also means depth: one who climbs high

above is also one who is going deep within to know his “self” or khud / khudi.

Education is also to be

blamed. Modern education, to be precise. We just have too much data and

information, we know too much but, paradoxically, remain unenlightened and

unhappy as most of our social, economic and especially ecological indicators

reveal. Or, we know a lot about things that don’t matter---the trivial and the

accidental, always in search of answers for the how questions--- but almost

nothing about what is essential, the why questions. Our instrumental reason,

the reductionist rationality, while efficient, practical and useful in the

abundant production of material products, nevertheless, destroys something

deeper and qualitative that can be termed wisdom or hikma in Islamic languages

and societies. This system of teaching-learning is so crudely quantitative that

only what we can see, measure, control and predict is what exists for us. It

teaches us to see everything with one-eye only.

It is like casting a fish net in the sea and what the net brings up to

the surface is all that exists. Everything else that passes through the net is

non-existence for us. Moreover, an education that is obsessed with

practicality, is exclusively oriented towards the achievement of the

quantitative and celebrates materialism and consumerism without any regard for

non-material or spiritual values (iqdaar) “makes man a more clever devil” as

C.S. Lewis once remarked.

Waleed El-Ansary has

argued that Muslims used to teach numbers symbolically to children, somewhat

like this: One (1) means God/Allah, two (2) means man and woman, wife and

husband, father and mother, night and day, three (3) means you, mother and

father, or, God, The Holy Book and The Prophet (pbuh), four (4) means…and so

on. We have come a long way from those times, the “dark and primitive ages”. We

have become enlightened, progressed and developed ourselves to (symbolic)

death! We have turned every form of quality to quantity. No symbolism. Just,

sheer quantity. We no longer aspire to climb up, but are happy to dwell in dark

basements of our being (wujud), our ego. Kids now learn their arithmetic as

follows: One (1) means me, and only me, means 1 big house, 1 big car…, two (2)

means 2 mansions, 2 iPads or 2 million Rupees or Dollars…, three (3) means

three pairs of Nike sneakers… and so on. In the “Christian” west, this loss of

symbolism can be clearly seen in the reduction and quantification of an

essentially symbolic and qualitative event, Christmas, which is now reduced to

crass forms of consumerism. Our own Eid, Eid al Fitr and Eid al Azha, for

example, also seem to be following that trend. I will end this blog post with this lament of

T.S Eliot from his poem The Rock:

All our knowledge

brings us nearer to our ignorance,

All our ignorance

brings us nearer to death,

But nearness to death

no nearer to GOD.

Where is the Life we

have lost in living?

Where is the wisdom we

have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge

we have lost in information?

The cycles of Heaven in

twenty centuries,

Bring us farther from

GOD and nearer to the Dust.

(From T.S. Eliot, The

Rock)